You might have heard it said that the opposite of empathy is apathy. And that’s not wrong. But what often gets overlooked, what gets missed, is the third leg of the stool: sympathy. It’s important that, as leaders and change-makers, we understand all three — and the impact they each can have.

I call sympathy the third leg of the stool because without a clear understanding of the two, people often confuse empathy with sympathy. Sympathy is feeling bad for a person: “Wow, you got hit by a truck. That sucks.” Empathy takes it a step further: “I’ve been hit by a truck before, too, and I know how horrific it is.” Empathy is personal experience that allows us to connect with and understand what the other person is feeling.

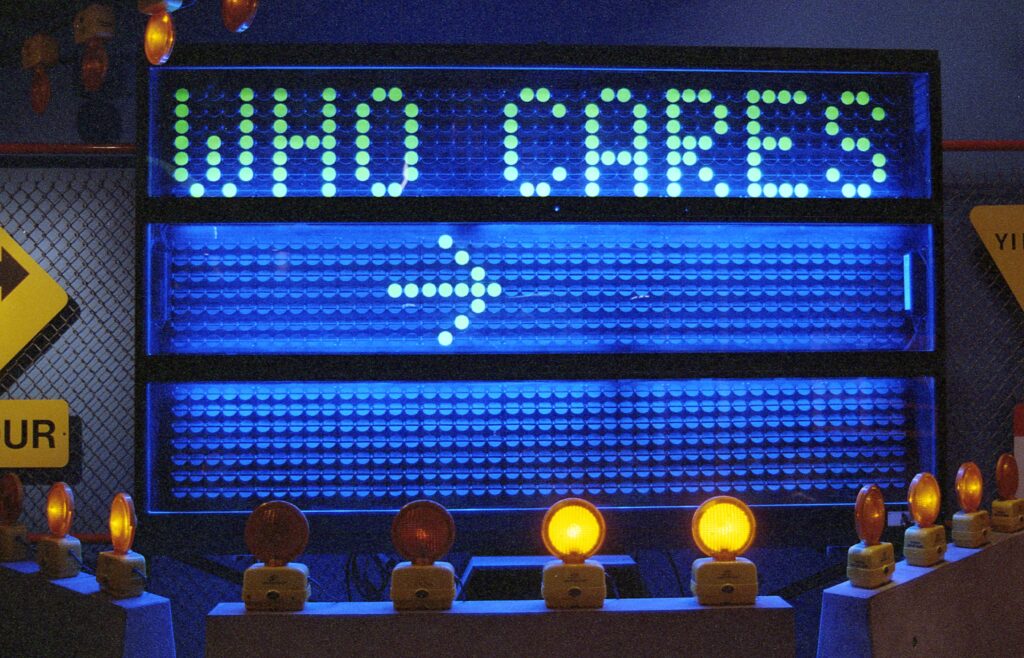

On the other hand, if I’m apathetic, my response to your being hit by a truck might be, “Okay, you got hit by a truck. So what?”

The common perception of apathy is that it’s the direct opposite of either sympathy or empathy, both of which require some semblance of emotional positivity. In order to have sympathy or empathy, you have to feel something.

Apathy, on the other hand, is the absence of feeling. In an apathetic state, by definition, one lacks interest, enthusiasm, or concern. An apathetic person can’t stir up an emotion, and to the person on the receiving end, that can feel cold, dismissive, and, sometimes, even like gaslighting.

When I experience someone who is apathetic, it feels intentional, like they’re deliberately undermining my experience and feeling as invalid, unnecessary, negated. But that’s not what the definition says. What I think is really happening is that we are mislabeling what is real for what we think is apathy.

The big question here, the one I’d ask my coaching clients is, SO WHAT? What does it matter whether a person is “apathetic,” empathetic, or sympathetic? It matters what we do with what we find out about this answer. In some lower-stakes relationships, the answer isn’t all that significant. But if it’s more serious than this — if, for instance, the person is a decision maker, a leader, or a person of influence — the answer matters a great deal.

An apathetic person in a position of power can be incredibly damaging — and could very well be an insight to something more serious for the person. Assuming they haven’t just gotten terribly bad news and lost the will to live, the challenge here is this: How can we move that person from a place of apathy — a complete lack of interest or concern — to at least a place of sympathy? Or, even better, empathy? Because as powerfully disconnected as apathy can be, empathy is equally powerful because it actually connects people by lived experience. It’s hard to beat that.

Powerful as empathy is, however, it’s important to understand that apathy is not an inherently negative state of being. It’s a state of disconnection. Not caring is not the same as wishing to cause harm.

What I think often gets labeled as apathy is actually a good thing because, basically, they’re like Dr. Spock — completely rational, unencumbered by emotion. They don’t intend to gaslight or be cold. Their intention is to be objective, factual, and emotionally neutral.

About being hit by a truck, that person may simply ask, “did that hurt? How did it hurt?” In fact, this kind of apathetic person may be so mechanically curious that they forget to fill in the blanks about the human experience.

There are people who use their apathy aggressively, asking questions that feel offensive, thoughtless, or mean. But apathy, by definition, doesn’t actively cause any real harm.

Consider the Core Values Index™. Some people who are seen as apathetic might fall into a Builder or Innovator sort of role.

A Builder values power — not the absolute kind like that of a king or dictator — but the power within themself to a) know what to do and b) have faith in themself that it’s the right thing to do to serve the greater good. They aren’t necessarily thinking about the other person; they’re thinking about what they themselves can contribute and bring to the table to improve a situation.

The Innovator is like the absent-minded professor or a triage nurse on a battlefield. They take in tragedy, filter it — almost without emotion — and rank and order responsibilities to move forward, come up with wise solutions, and design options that help make effective decisions and get things done.

If I’m an “apathetic” person for reasons not nefarious — meaning I’m naturally apathetic and not psychotic — there’s a normalcy for me in being objective, clinical, and data-driven. I don’t know how to be in touch with emotions in the way others might expect me to. Despite how often I hear it called such, this is not apathy.

For those of us who are emotional, we need people to feel with us. We’re drawn toward the sympathetic and empathetic. To feel the absence of that — to feel like we’re being met with, well, Spock — can be devastating.

If that’s you, it’s important to consider that apathy can be good and bad, just as there is good stress and bad stress.

Anthony De Mello, an Eastern mystic and Catholic priest, teaches that stress is good and bad. The good stress is that which empowers us and makes us sharper, stronger, more alert, and more aware. Bad stress debilitates, inhibits us, and bothers us.

I think there’s a correlation between De Mello’s view of stress and how we ought to view apathy.

In reality, we probably encounter genuine apathy a lot less often than we realize. It may empower or inform us of a better decision, in which case we can view it as good.

It’s not until it bothers us that apathy is a problem.

De Mello believes that if we can learn to become conscious of when we’re bothered or triggered by something, we can recognize that discomfort as an indicator that it’s moving us away from something or toward something.

But what would it look like if we weren’t bothered? How would it enhance, sharpen, and wisen us to ask better questions or engage differently?

This isn’t to say that you should accept apathy at face value or assume that it’s always productive. Because it’s not. But apathy as a whole has gotten a bad rap. And I think it deserves some more consideration. We give plenty of credit to empathy and sympathy because they’re nice and likable and easy to get along with. But apathy deserves a seat at the table, too.

Next time you’re feeling frustrated by someone’s apathy, consider where they’re coming from and how their apathy might be helping the bigger picture. And next time you’re tempted to respond to a situation with raw emotion, consider what it might look like to approach that situation with a bit of apathy? What would it look like not to be bothered?

And does it change how you think about apathy?

Photo by Peter Conrad on Unsplash